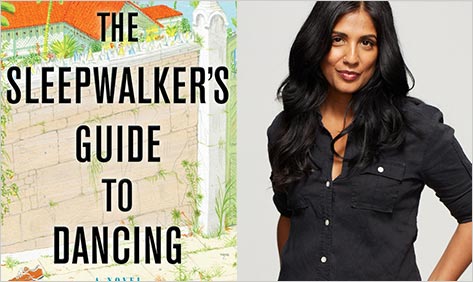

The Strangest Sort of Surgery: Mira Jacob

We love Mira Jacob’s debut novel, The Sleepwalker’s Guide to Dancing.

We love Mira Jacob’s debut novel, The Sleepwalker’s Guide to Dancing.

Dazzling and irreverent, witty and profound, this is a family saga of the most engaging kind: heartbreaking, hopeful, and alive on the page — which is why we had to make it one of our Summer 2014 Discover Great New Writers selections. The Anglo-Indian story of the Eapen family cuts across decades — beginning in 1970s India, through the 1980s in Albuquerque, to Seattle in the ’90s — as they wrestle with their futures and make peace with their shared past. Readers will undoubtedly be reminded of Jhumpa Lahiri’s work, but we’ll also suggest you read A Sleepwalker’s Guide to Dancing if you loved the insight and humor of J. Courtney Sullivan’s Maine, Jean Kwok’s Girl in Translation, or Maria Semple’s Where’d You Go, Bernadette.

Here’s Mira Jacob on storyboarding plot, finding her characters, her “brilliant writers I should have known about earlier moment,”and more for the Barnes & Noble Review. —Miwa Messer

Was there any specific person or event from your own life that influenced this novel?

I started this book with the vague notion that it was going to be about a man, a father, receding from his reality in some way. The father I had originally written was quite different from my own for the obvious reason that I was writing a novel, not a memoir, and I was of the firm mind that keeping characters fictional is what allows writers to grow and breathe with them, to let them surprise us, and to take the story in places we can’t anticipate. Then, four years into writing the book, my own father started dying from renal cancer. I couldn’t even look at the book in those years — it felt too cursed. I was also barely functional, as maybe all people are when they are watching someone they love die slowly and painfully.

A year after my father died, I went back to the book and did something I was sure was nuts: I ripped out the old father and put in mine. It was the strangest sort of surgery, because the events in the book didn’t happen to my father, but there he was on every page, answering for them as if they had. He had a different wife, a different son, a different daughter (Kamala, Akhil, and Amina are wholly fictional) and yet he was so perfectly himself, with his mannerisms and faults and generosities, that I felt like I was getting to see him alive again.

Why did you decide to tell the story in chapters with alternating timelines?

I didn’t originally — that solution only came up after I was told by a few trusted readers that the high school section (which came as one big chunk in the middle of the book) wasn’t working. It was killing the momentum. Some even suggested I kill it altogether, which was heartbreaking to me. (I’m generally not so precious with my writing — I killed another 250 pages of the book without a backward glance, but this just felt different.) In my mind, the two stories were simultaneously unwinding mysteries that somehow needed to play off of each other, I just wasn’t sure how. My husband [documentary filmmaker Jed Rothstein] listened to me worrying about this aloud one day and said, “You should storyboard the plot.” I had never done that before, so he gave me a basic primer and afterward I went and bought a bunch of colored notecards and went at it like a woman possessed. It was terrifying, exhilarating, and in the end, really, really fun.

In writing The Sleepwalker’s Guide to Dancing, tell us what you found effortless to write about and what you found to be the most difficult to write about.

Effortless: Kamala. I have no idea where she came from but once she arrived, she dictated everything else that happened around her. And she was completely inflexible! I would have a nice intellectual conversation with myself about how a scene should go and then Kamala would show up with her own list of demands and her strange, fraught heart. And I would just do whatever she said.

Difficult: Romantic love. For me, it’s like writing about a sunset. Yes, it’s beautiful, but who needs me to tell them that?

Photography plays a large role in the protagonist’s life. Why have you chosen to make photography a central art form and theme for the novel?

Photography is an act that is equal parts passive and active. You’re the watcher, the stalker, the conduit, the medium. The one thing standing between what is seen and what will slip by unnoticed. So it’s the perfect outlet for a girl whose helplessness over the past, whose guilt and anger and fear have held her in suspended animation for years. It’s the place her particular brand of aggression can flourish.

Whom have you discovered recently?

I am having the great joy of reading Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah right now. I love it so much I have rationed the pages. Then I am on Okie Ndibe’s Foreign Gods Inc., of which I’ve read the first chapter and cannot wait to continue. I suppose some would say I am having a Nigerian moment, except that I am actually having a “brilliant writers I should have known about earlier” moment.

Miwa Messer is the Director of the Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writers program, which was established in 1990 to highlight works of exceptional literary quality that might otherwise be overlooked in a crowded book marketplace. Titles chosen for the program are handpicked by a select group of our booksellers four times a year. Click here for submission guidelines.